A decade ago, event-driven architecture was the wild west. Documentation? It’s in a spreadsheet somewhere. Where did the event go? Here’s a list of ten logs to search through. How do we make sure events from System A can be understood by System B? Slap some headers on the message and hope that they make it across the event broker.

Thankfully, the increased adoption of event-driven and distributed architectural patterns has meant increased attention to related open-source specifications. With solidifying specifications, standardized instrumentation and reusable tooling has emerged as well. Becoming event-driven today involves less guess work and more assurance of compatibility.

But which specifications matter? And how should they be used?

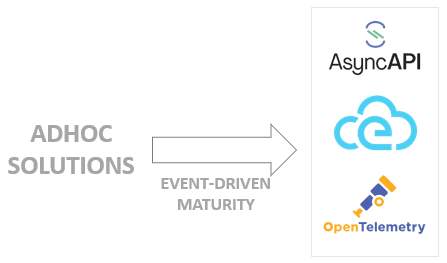

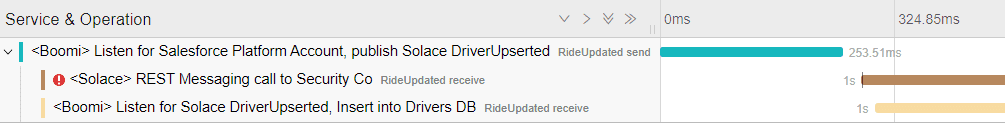

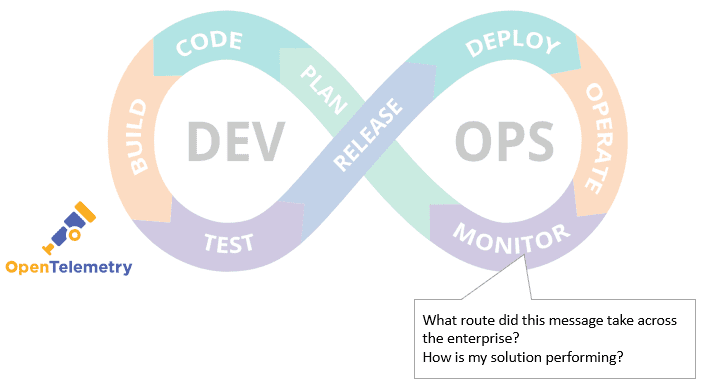

Within the event-driven ecosystem, there are three major emerging specifications: CloudEvents, OpenTelemetry and AsyncAPI. Each of them map to phases of the DevOps lifecycle, and address a distinct challenge with event-driven development and/or implementation. Used together, they can make event-driven DevOps easier to implement.

Here’s a summary of where each of the specifications fits, I will examine each more in depth later:

In addition to different portions of the DevOps lifecycle, the three specifications focus on different challenges and objects within the event-driven landscape:

| Specification | Focuses On | Challenges Addressed | Primary DevOps Lifecycle Phase |

|---|---|---|---|

| CloudEvents | Messages | Interoperability of events between different services platforms and systems | Code |

| OpenTelemetry | End-to-End Traces | Understand performance and behavior of distributed architectures (both sync and async) | Monitor |

| AsyncAPI | Applications | Describe and document message-driven APIs | Plan |

There is some overlap between the three, particularly as the specifications mature and expand. There are areas where two specifications cover the same ground in different ways, so it’s up to architects to determine how best to allocate functionality.

AsyncAPI

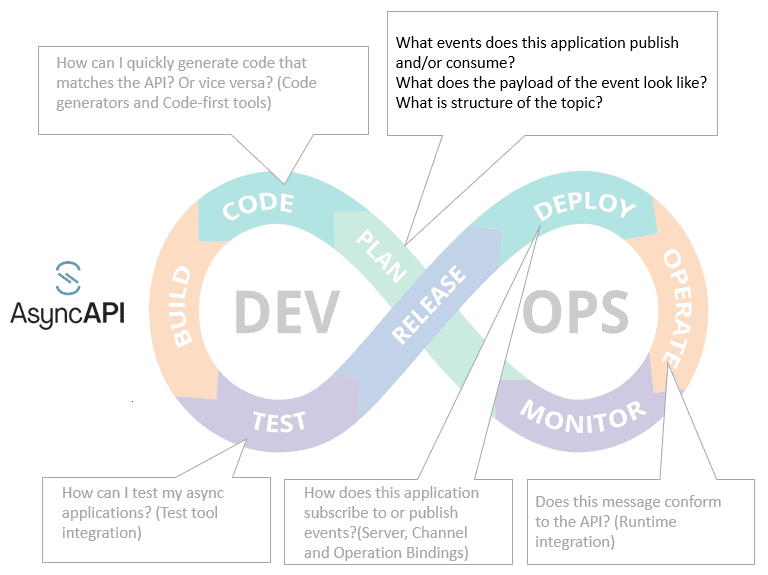

Particularly in API-first methodologies, the DevOps “Plan” phase revolves around defining the application programming interface (API). The API describes what messages an application can accept and emit. The APIs can then be used to build the application, advertise its capabilities to others and document its functionality.

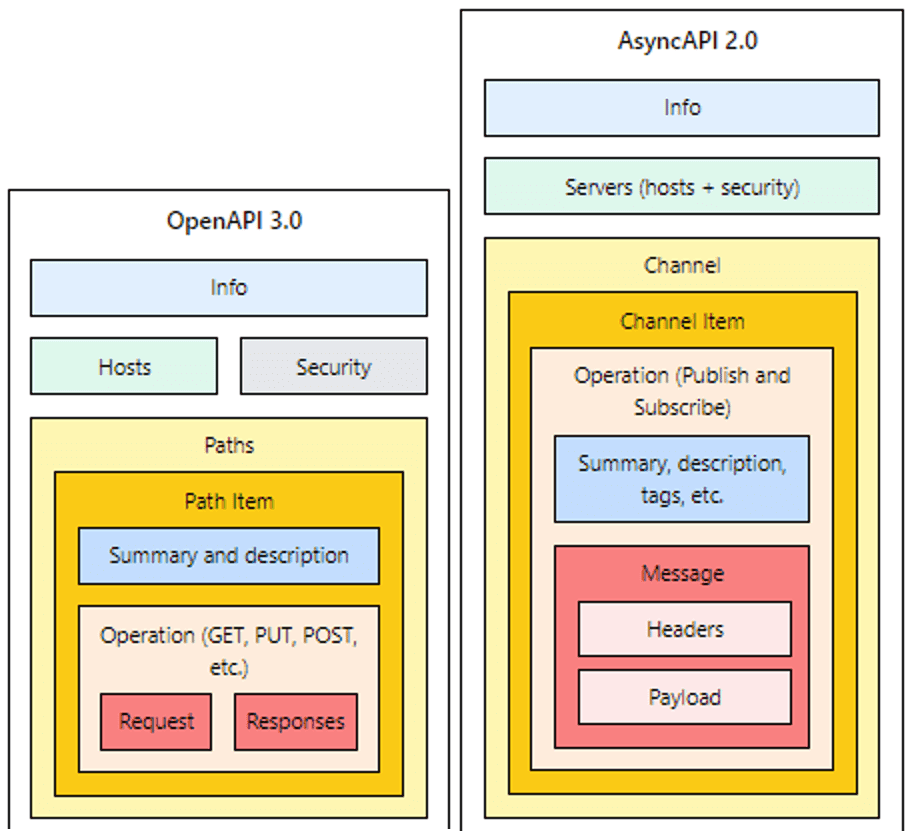

However, defining an interface requires having a standard way of describing it that can be 1) used by many different programming languages, 2) leveraged by multiple tools and 3) read (at least sort of) by humans. In the synchronous world, OpenAPI does this work. For event-driven applications, AsyncAPI tries to do the same thing. It offers a parallel to the OpenAPI specification, but with modifications to allow for asynchronous, event-driven behavior. You can see the parallel for yourself in the structure of the specifications:

Figure 3- OpenAPI vs AsyncAPI (via https://www.asyncapi.com/docs/getting-started/coming-from-openapi)

The key difference between the two spec is AsyncAPI removes OpenAPI’s assumption that a request is tightly bound to a reply. Instead, AsyncAPI’s “channel” concept represents an address that the application’s clients can either publish to or subscribe from (In many message broker situations, the “channel” equates to a “topic”.) Published and subscribed messages are decoupled from each other, allowing for asynchronous interactions.

Another distinction: asynchronous patterns can rely heavily on headers to preserve state and context that otherwise would be lost due to decoupling. To address this in AsyncAPI, messages that are either published or subscribed can be associated with two schemas: one for the header meta-data and one for the body of the message.

Here are some questions that AsyncAPI can help you answer during the plan phase:

In addition to the Plan phase, AsyncAPI also has emerging capabilities for other phases (shown in grey above):

- Code: A code-generator for Spring Cloud Stream takes an AsyncAPI definition and creates skeleton code, reducing the need to laboriously create boilerplate code. More code generators are planned. And vice-versa, there are code-first tools at that will generate an AsyncAPI spec out of numerous popular languages.

- Test: The partnership between AsyncAPI and Postman highlights the increased ability to test async flows once they are well defined.

- Deploy: Technology-specific bindings defined within the spec can be used to establish connections and subscriptions to event brokers upon deployment.

- Operate: Once messages are flowing at runtime, an AsyncAPI document can be used to ensure schema compliance.

CloudEvents: Aiming for Operational Interoperability

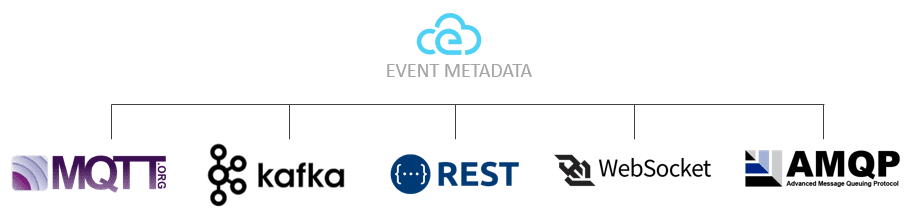

As more technologies become event-driven, ensuring that they all communicate effectively becomes challenging.

For example: An equipment failure occurs at a manufacturing plant, generating an event. The attached IoT device publishes a message containing the alert event to an MQTT server. At the end of the journey, the event lands in a Kafka topic, is pushed to a websocket, and is sent to a function as a service using an HTTP webhook.

Contextual information about the event is crucial for all the consumers, but every consumer could expect it in a different place, with a different naming convention and a different format. Some producers might even choose not to include a key piece of metadata.

To resolve these challenges, enterprises have traditionally created their own custom envelope: standards about what meta information is included in messages and in what format. But many applications don’t comply, either because they are outside the organization, it’s a legacy app that’s too pricey to retrofit, or because they use a protocol that hasn’t been included in the standard.

The workaround is typically tedious and error-prone – manual mapping of metadata. This additional step can mean using data transformation software to enrich messages. And in cases where information is missing, you either have messy data generation or make do without it.

CloudEvents aims to eliminate the metadata challenge by specifying mandatory metadata information (like event source and type of event) into what could be called a standard envelope. The fields are then mapped to individual messaging protocols like Kafka, MQTT and HTTP, so there’s no question about where the fields exist on each message. Most importantly, there’s wide support for different programming languages.

There is an overlap between CloudEvents and AsyncAPI, as noted by AsyncAPI’s founder. The metadata fields used by CloudEvents could be defined within an AsyncAPI schema. However, there is an advantage to using CloudEvents in addition to AsyncAPI. CloudEvent libraries are available for multiple programming languages for multiple protocols, which streamlines interoperability. For instance, a Java developer can utilize a CloudEvents SDK to publish CloudEvents compliant messages to Kafka, without having to worry about the underlying metadata implementation.

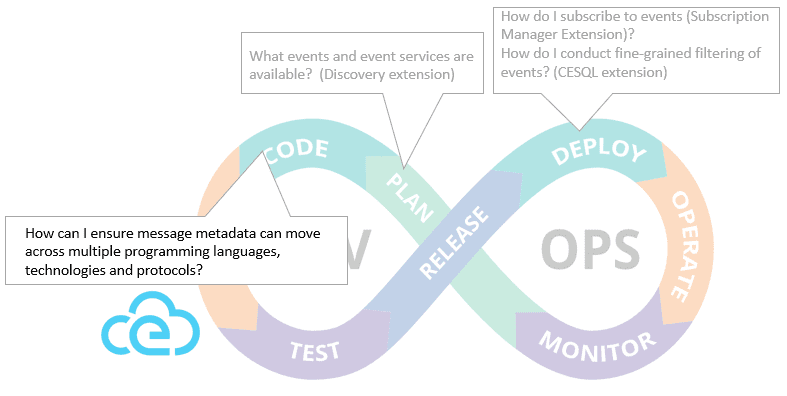

And as an evolving standard being used by major SaaS and cloud providers, CloudEvents is gaining both momentum and functionality. In addition to the Operate phase, now that the core specification has been released, the group’s focus has turned to several extensions that address other stages and address other event-driven challenges:

- Plan: Discovery capability allows new and existing applications to query a catalog of services for available events using a standardized API.

- Deploy: Subscription manager capability allows applications to subscribe to events using a standardized API.

OpenTelemetry

In contrast to AsyncAPI and CloudEvents, which address producing and consuming events themselves, OpenTelemetry focuses on end-to-end monitoring of those events. OpenTelemetry standardizes the creation and management of trace information, which can reveal the path of a single event through multiple applications, or show the aggregate metrics that combine multiple events.

Implementing OpenTelemetry typically means instrumenting code so that it can emit monitoring information. This information is then aggregated in a backend system, either on-premises or through monitoring as a service provider.

Once completed, OpenTelemetry helps to answer the classic event-driven question “Where’s my event?” By including business-related fields in the trace, it’s possible to search by, say, the order number of the original event, and have its entire path through multiple applications revealed.

There is minimal overlap with the CloudEvents and OpenTelemetry. In fact, CloudEvents has explicitly stated that it does not want to be involved with tracing, and its headers should not be used for it.

Conclusion

It’s a great time for event-driven architecture. Challenges that used to be overcome in different ways in every implementation are now being addressed by standard, open-source solutions. While OpenTelemetry, AsyncAPI and CloudEvents do have overlapping capabilities, they are distinct enough to all warrant a place in your DevOps processes.

Explore other posts from categories: DevOps | For Architects

Jesse Menning

Jesse Menning